During a 2018 firefight, the leader of a team of Army Rangers on patrol in southeastern Afghanistan used his body to shield a U.S. crew in the cockpit of a medical evacuation helicopter from enemy machine gun fire. It would cost him his life.

“His final display of bravery, courage, and selfless devotion to his troops is the most honorable thing I have witnessed,” said a fellow Ranger, a seasoned combat veteran, in a written account of the battle.

Sgt. 1st Class Christopher Celiz was protecting the chopper and its crew so that a wounded partner force member could be transported for medical care, and so that the MEDEVAC would not be shot down, which would have caused a greater loss of life, said the fellow Ranger.

The unnamed Ranger’s account is among records U.S. Central Command has finally provided me under the Freedom of Information Act, nearly four years after I requested them and just two short years after I sued for these and dozens more documents.

The record contains first-hand witness testimony, gathered in the days after Celiz’s actions, that paints a picture of U.S. special operations soldiers’ unwavering courage in the face of heavy enemy fire.

“SFC Celiz lived the Ranger creed until his last moment,” the investigator concluded after interviewing witnesses and reviewing the evidence.

A soldier’s story worth sharing

Celiz, a 32-year-old on his fifth combat deployment, was later medically evacuated from the battlefield himself on that morning in July 2018. But he later died of his wounds.

News of his courage soon reached the Pentagon. Then-Vice Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army, Gen. James C. McConville learned of it from his own son, an emergency helicopter pilot, the Army said in a statement.

In late 2021, Celiz was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for his bravery. That news, however, seems to have been somewhat overshadowed by the fact that President Joe Biden presented Celiz the medal on the same day he bestowed the nation’s highest honor for valor in combat on Sgt. 1st Class Alwyn Cashe and Green Beret Master Sgt. Earl Plumlee.

Many veterans and service members felt Cashe’s battlefield heroics in Iraq in 2005 had been unjustly overlooked or undervalued for far too long, and there was significant anticipation for his posthumous award in the months leading up to the December 2021 ceremony.

Celiz’s sacrifice in Afghanistan was much less well-known. The fact that the awards ceremony took place just months after the U.S. withdrew in chaos after more than 20 years of war there likely diminished the public attention given to his story.

The CENTCOM records show why it’s a story worth telling.

“Promise me you won’t be a hero”

The day Celiz left for his seven-month Afghanistan deployment in 2018, his wife asked one thing of him: come home.

Chris had met his future wife, Kati, during high school in 2002. The two worked together at a local grocery store in Summerville, South Carolina.

At the store one day, Katie’s jacket disappeared. When she returned from a break, it had mysteriously reappeared again. The same pattern played out over and over for a week.

Then one day she saw Celiz pushing carts. He was wearing the jacket. Later, when she got back from break, the jacket was in the break room, laced with rose petals.

“I thought it was cute,” she said in the Army statement.

The couple married in 2007, the year Celiz joined the Army. Their daughter Shannon was born in 2010.

Celiz had attended The Citadel from 2004 to 2006, the military college in Charleston, South Carolina, said in 2022. He left school to pursue ambitions of being a Special Forces soldier, the Army said.

After years serving in conventional units, Celiz was selected to serve with the 75th Ranger Regiment in 2013 as a combat engineer with the 1st Battalion at Hunter Army Airfield, Georgia, an Army biography states. In 2017, he was assigned to serve as a mortar platoon sergeant in Company D.

Celiz’s 2018 deployment was his fifth as a Ranger, his seventh since joining the Army.

“Promise me you won’t be a hero,” Katie Celiz told him before he left. “Just come home to me, no matter what.”

But Chris Celiz couldn’t make that promise.

“You know I can never promise what’s going to happen,” he said.

Journalist Wesley Morgan reported in Politico that Celiz was part of an elite group of U.S. Special Operations Command troops supporting a CIA-led program, known as ANSOF, that employed Afghan commandos to kill or capture terrorist targets.

While he was away, Celiz sent emails and hand-written letters to his wife. He recorded videos of himself reading for his daughter, Shannon.

When Shannon turned 8 that summer, he told his family he probably wouldn’t be able to call home. But he did anyway, making time for to FaceTime with her.

He told Katie and Shannon he loved them and he would be home soon.

A ‘secret mission’ with ‘partner’ forces

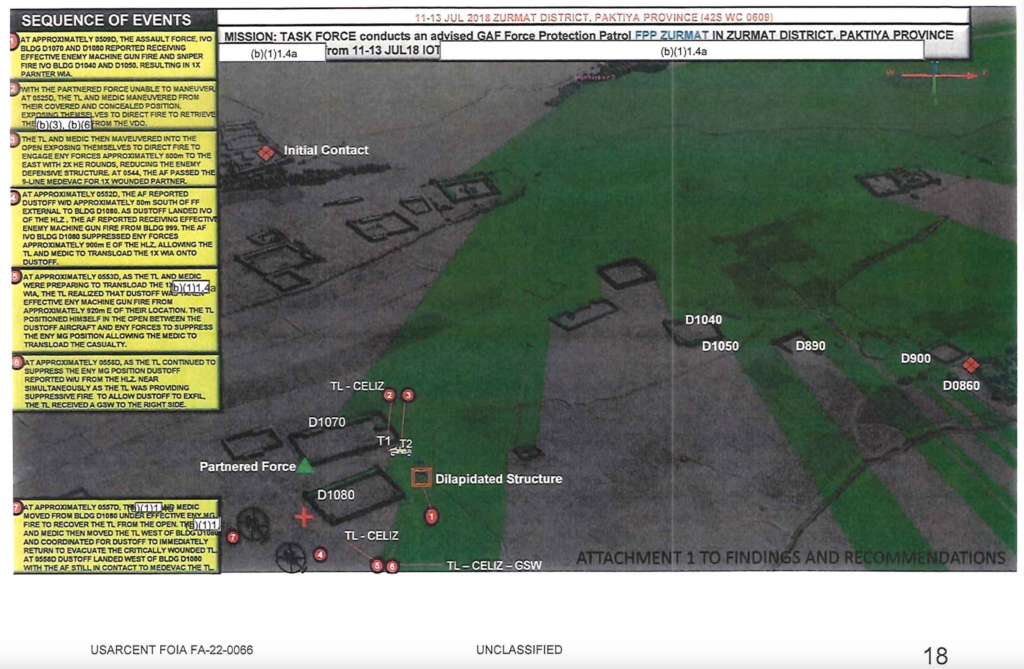

Weeks later, on July 12, 2018, Celiz was the leader of a four-Ranger team on his final mission, advising and assisting Afghan partner forces on an early morning security patrol in Zurmat district of Paktia province southeast of Kabul, near the border with Pakistan.

Militant activity in the area had historically involved a Taliban commander and a facilitator for the Haqqani network, according to human intelligence reporting cited in the CENTCOM records (their names are redacted). The area had been used to support attacks on the district center and Gardez, the provincial capital, the intel said.

The U.S.-supported clearance operation was meant to show that friendly forces could secure the area, the CENTCOM records state.

Celiz’s team included a medic, a radio operator (RTO), and a fourth Ranger I will call the “seasoned combat veteran,” for lack of a better term.

You see, CENTCOM has redacted from the document all names and ranks and nearly any other title other than Celiz’s (and apparently even some of his), citing FOIA exemptions that protect privacy or, in some cases, national security.

In 2022, the Army identified the RTO on the mission as Garrett White, a second lieutenant at the time of the statement. Because of uncertainties caused by CENTCOM’s redactions, however, I will refer to him as “the RTO” where I am quoting from the documents, to avoid unintended misattribution.

White was a young enlisted soldier on his first deployment in July 2018. One of the other Rangers was on his fifth deployment and the other was on his second. During that deployment, they’d each been on 20 or more missions across Khost, Paktia, Paktika, and Jowzjan provinces.

The narrative that follows is reconstructed from these three Rangers’ accounts, but may contain slight errors because of difficulties distinguishing references to different individuals.

In fact, citing national security classification, CENTCOM has redacted several instances of a word or words describing the “partner” forces, though typically that term was used to describe Afghan troops and at least one spot in the report does say they were Afghan forces. In the other cases, terms could be obscured because they refer to a classified program or somehow point to the CIA or a similar agency.

ANSOF teams of CIA surrogates, supported by Rangers, often targeted al Qaeda cells in Khost and Paktia provinces, Morgan told Coffee or Die Magazine in 2021. Author of the book The Hardest Place about U.S. counterinsurgency efforts in Afghanistan’s Pech Valley, Morgan is well-versed in such shadowy operations.

Indeed, the partnered operation in Zurmat district in early July 2018 was a “secret mission,” the Army’s 2022 statement said.1

“We’re on their turf. They know where we are”

Just before dawn, the ground assault force was nearing its dismount point, or vehicle drop off (VDO), to conduct reconnaissance and clearance of compounds they would use for a command and control element and [redacted] section.2

The Americans’ night vision capabilities gave them an advantage in the dark, White said in the 2022 Army statement about the mission.

“Once it starts getting light… we’re on their turf,” White said. “They know where we are.”

At their final checkpoint, overhead surveillance alerted the Rangers that an armed enemy fighter was laying in wait within 150 meters, the seasoned combat veteran said. An airstrike killed one enemy combatant.

After dismounting their vehicles, the patrol cleared their first area of interest. The Rangers, in two gun trucks, then drove up to link up with them and take up a position in a dilapidated building for overwatch and command-and-control of the clearance of a second area.

Daylight was beginning to peak over the mountains at about 5 a.m. when the U.S. and partner forces started taking heavy machine gun and sniper fire from compounds less than 1,000 meters to the north.

A member of the partner force was hit in the chest and critically injured in the initial barrage of 10 to 15 round bursts. The volleys of gunfire were coming every 10 seconds or so, the Rangers recalled.

“The rounds were over our heads initially and were being walked down,” said the RTO.

The driver’s side window of one of the trucks was hit in the initial contact. The Americans began shooting back from behind cover.

The Rangers gain fire superiority, call for a MEDEVAC

After the Americans returned fire at the known or likely enemy positions, they saw a dust trail, suggesting the enemy sped off. But the U.S. air support (in the document as “AWT,” or air weapons team) couldn’t spot their vehicle.

Within a minute or two, the ground force began taking fire from the east. To turn the tide against the remaining fighters, Celiz split his four-man team into two elements: two would provide covering fire, while he and the medic would bound to a gun truck to grab a recoilless rifle.

Braving the steady enemy fire, Celiz retrieved the heavy weapon from the bed of the truck and fired it twice, destroying a compound 600 meters away. This allowed the Afghan forces to better maneuver to engage the enemy.

Hostile gunfire quickly died down to sporadic, said the seasoned combat veteran. A “watch and shoot rate” of fire, the RTO said.

During the lull, Celiz and the medic bounded to where the wounded partner force soldier was being treated. He had a sucking chest wound, but the medic said he could keep him alive on the ground for a little while.

Eventually, the Rangers regrouped. Given their fire superiority, Celiz decided to coordinate a medical evacuation, and the other Rangers set up security for a landing zone.

But the helicopter landed about 75 meters shy of its mark.

Then the enemy opened up with machine gun and sniper fire. Every few seconds, bursts of six to nine rounds were hitting the ground within 20 meters of the MEDEVAC, the seasoned combat veteran recalled.

“The enemy fire was zeroed in on where DUSTOFF was wheels down,” recalled the team medic, referring to the MEDEVAC by military slang that originated in the Vietnam War.

What happened next was nothing short of heroic.

The “fully exposed” Rangers protect the MEDEVAC

Amid the enemy fire, the RTO and the seasoned combat veteran stepped out from their building and away from their gun truck, “standing fully exposed” while providing suppressive fires, said the seasoned veteran.

Then, as Afghan troops began carrying the wounded soldier on a litter to the MEDEVAC helicopter, the team medic ran out to give the DUSTOFF crew an update on the casualty.

“But my main intent was to intimate to the crew that they were taking accurate fire and needed to leave as quickly as possible,” the medic said in his statement.

The RTO watched as the medic moved under heavy enemy fire.

Celiz also ran out, all the way to the MEDEVAC’s door, providing suppressive fires along the way.

“With disregard for his own life, SFC Celiz trailed the litter team and ran all the way to the door of the aircraft to provide cover fire,” the RTO said.

Then the RTO ran out, too, stopping 10 meters from the nose of the bird.

He fired off dozens of rounds in about a minute, “standing fully exposed to the enemy PKM fire in order to provide as much fire superiority” as he could until the medic, litter team, and Celiz could return to cover, said the seasoned combat veteran.

At this point, all four Rangers were exposed to heavy enemy fire. The seasoned combat veteran was 15 meters from cover, the RTO was 10 meters from the helicopter’s nose, and Celiz and the medic were at the door of the MEDEVAC.

“I yelled ‘pneumothorax’ at the flight medic and sprinted back, hoping that they recognized my urgency to get out of the dangerous area and would follow suit,” the Ranger medic recalled.

As the medic ran back for cover, he passed Celiz and the litter team. As he then passed the RTO and the seasoned combat veteran, those two peeled back to cover as well.

Returning to cover, the RTO stopped short of ducking behind the gun truck when he turned to see Celiz still standing ground at the door of the helicopter.

“…no regard for his personal safety…”

The medic also turned back to look at the helicopter. Celiz was still there, “providing a high volume of suppressive fire.”

“With no regard for his personal safety and the valiant effort to keep the aircraft, crew, and litter team safe, SFC Celiz continued to engage the enemy until the litter team had finally finished loading the casualty up,” the medic said.

Although still exposed, the RTO and the seasoned combat vet began calling to Celiz to move back to cover. The RTO changed magazines and began moving closer to the helicopter to help suppress the enemy fire, he said.

Now the litter team passed him.

Now Celiz was at the cockpit.

He was “providing a physical barrier between the enemy and the pilot,” the RTO said.

The gunfire hitting the ground around Celiz was sending up plumes of dust, the 2022 Army statement.

“The ground looked like it was boiling,” White was quoted saying in that statement.

As the helicopter began to power up, Celiz finally turned back for cover, hostile fire “impacting right at his feet,” the medic said in his witness statement. “He was immediately hit.”

Celiz fell to a knee. But he waved the MEDEVAC off.

Then Celiz collapsed to the ground. He pulled himself up one time with his arm before going unconscious.

His friends continued to call to him, but he didn’t move.

Lifesaving efforts fail

Two of the partner forces, likely Afghan commandos, ran out “into the hail of bullets” to try to pull Celiz to safety, the medic said, but they weren’t able to move him.

“By this time the aircraft was airborne,” the medic said.

The RTO picked up his rate of fire while moving to Celiz with his teammates. Together, they were able to drag their downed team leader some 40 meters to cover.

But as the RTO coordinated to keep the MEDEVAC in the airspace, the enemy fire became rapid and began impacting with in 20 meters of their position.

Celiz was pale and unresponsive.

They stripped his body armor, cut the sling to his weapons, and began to sweep for bleeding. The medic said Celiz had likely been hit in a major organ.

The only thing they could do to save him now was get him to a field hospital, the RTO recalled the medic saying.

DUSTOFF was able to land again, this time in a more protected spot closer to the compound. The Rangers hand carried Celiz until three partner force soldiers brought them a litter. They got him loaded and the bird took off again.

Three minutes had passed since he was shot in his right side. He would arrive at the field hospital within about 10. A medical team worked on Celiz for nearly two hours.

“Upon entry into the chest, the surgeon discovered two large injuries to the right ventricle,” the incident’s investigating officer found. “While there were some moments of heart activity during the surgery, SFC never regained cardiac activity.”

He was pronounced dead at 8:02 that morning.

“SFC Celiz exposed himself multiple times that morning and made himself a physical barrier between the enemy and the aircraft,” the RTO said. “His actions were those of valor and courage. He made selfless decisions that day in order to save multiple lives.”

“The enemy returned to a watch and shoot for the remainder of the operation,” he added.

Back home

At the family’s home in Savannah, Georgia, Katie Celiz was waiting for husband to return from his deployment when she heard a car door close in the driveway.

She rushed to the front steps, thinking it might be him.

But in an instant she knew he would not be coming home when she saw two uniformed soldiers walking to her porch.

“I just thought this can’t be real,” she said, quoted in the Army’s 2022 statement.

She remembers only bits and pieces of what the soldier said.

“It was my way of protecting myself,” Katie said. “Just shut it all off. Just listen, try to process it and move forward. Chris was very big on not dwelling on the past.”

He would say: “Push forward, never go back.”

Meanwhile, their daughter Shannon had been hiding, planning to surprise her dad.

She heard everything.

After his death, Celiz’s platoon mates would drive by the family’s house and check on his family regularly, the Army said. Rangers helped with Shannon’s school project and attended her school’s Hannukah play.

“They took her under their wing,” Katie Celiz said.

During a Bronze Star ceremony for Celiz on Hunter Army Airfield on March 8, 2019, then-Maj. Gen. Mark Schwartz, deputy commanding general of Joint Special Operations Command, placed the medal around Shannon’s neck.

In an Army video posted on Facebook in 2022, Katie Celiz said the Rangers will always be a part of her family’s life.

And while her young daughter has a lot of things she’ll list off wanting to be when she grows up — writer, teacher, painter — Katie Celiz said in the video, there’s one thing she always ends with: “I’m going to be a Ranger.”

The investigation records

Here are the 36 pages of records CENTCOM provided in response to my lawsuit. Citing privacy and national security, the government has withheld nearly 50 pages, which appear to provide additional operational and medical details.

FA-22-0066-Releasable-Docs- Of course, at that point in the Afghanistan War nearly every fucking mission was effectively secret because the military provided almost no media embeds or access to U.S. or coalition troops in the country, particularly those in special operations, and rarely provided the public with photos, videos, or written details of its combat operations carried out alongside Afghan forces. ↩︎

- I’m guessing mortars. ↩︎